by James Robinson

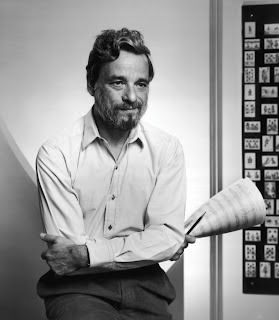

Anthony Sher as Richard III

Two in a week! That was the cry in 2016, that bleak mid-January

when we lost both David Bowie and Alan Rickman within 4 days of each other. Legends

both, musician and actor, yet both with personalities and a back catalogue that

inspired universal fondness and recognition - to the point that, when each

died, it was like losing a talented friend, not some demi-god from another

plane.

And here we are again. Two in a week (three, if you include Robert Holman, a consummate and lesser-known playwright, but more of him elsewhere). December has delivered the icy sting of loss in the shape of two of my heroes, and perhaps yours too. Stephen Sondheim changed my idea of musicals - Anthony Sher, of acting. Obituaries have been overflowing, as you’d expect, so rather than speak generally, it’s best to give my brief, personal impressions of their impact on me.

Without ‘Tony’ Sher, I would still have seen Drama as something loud and faintly obnoxious that rehearses in school halls. That was my impression up to Sixth Form, and nothing that I had seen as a result of those rehearsals gave me cause to think differently. And then, on a residential visit to Stratford-Upon-Avon, organised by a forward-thinking English teacher as a joint theatre/pub trip (different times), I found myself in the Swan Theatre watching some extraordinary-looking bloke prising his way up through the floorboards of the stage in a cloud of dust at the beginning of a little-known Jacobean piece of nastiness called ‘The Revenger’s Tragedy’. Sher was Vindice, on a mission of righteous murder against the Duke, and as a constant reminder of his motivation, carrying his poisoned fiancee’s skull around with him. This is where theatre started for me - that a performance could be not just entertaining, but thrilling, surprising, creative and….real. Perhaps ‘real’ should be in inverted commas - Sher specialised in intensely theatrical creations which often pushed at the boundaries of naturalism, and yet his skill was to bring these characters humanity, complexity and a scrupulous eye for detail, whilst never losing a magnetic connection with the audience. As he himself said: “You have simply got to be honest”, and perhaps honesty is a better word than real in this context.

Whilst there were some notable film and television performances, Sher was a theatre beast, and the theatre, most notably the Royal Shakespeare Company, was the place to really see the power of the man. I saw his Macbeth in 1999, over ten years after my first encounter with him, and he’d lost none of his intensity and craft. His ruthless, efficient and driven soldier was memorably at the mercy of his wife’s taunts and challenges about his courage and virility, exposing the soft belly under the hard shell and resulting in fits of defensiveness and struggles with conviction. Revealing the conflicts and contradictions of his characters was a specialty, and was again in evidence when I saw him in 2015 as Willy Loman in ‘Death of a Salesman’. This was a showman, a performer, a weaver of stories and mythology that capture his sons and deceive his wife - and covers the panic and fear building in his soul, revealed in the shape of sudden, unexpected rages that show a man slowly, agonisingly losing his grip. I’ve always loved his line, ‘You can't eat the orange, and throw the peel away, a man is not a piece of fruit’, and Sher’s delivery reeked of clammy desperation and complacency. Of course, he is probably most famous for his performance as Richard III, again for the RSC, and one of those ‘you had to be there’ moments in time (I wasn’t). A physical tour-de-force, played on crutches and giving the impression of a ‘bottled spider’, all brawny shoulders and arms together with that famous hunchback, and capable of deceptive, unnerving speed around the stage. If I write like I saw it, it’s because Sher wrote magnificently about how he created it in his book ‘Year of the King’, in my view the best book about the creative and research-based process of acting (Stanislavski might have something to say about that, but then again, you wouldn’t read his books for pleasure). Assisted by his brilliant drawings, keen self-awareness and humour, we are led from his early obsession with the character, seeing his shape and profile in mountains and dreams; his scrupulous work on the text, mined for meaning but also theatricality; his research into spinal deformation and scoliosis, leading to a hilarious argument with the ‘hump maker’, whose exquisite work Sher stuffs with padding so that the audience will actually see it; running full-speed down a raked stage on crutches, like a spider or bull or something in between, towards an audience who have never seen a Richard, or an actor, quite as weird, intoxicating and dangerous as this one.

In 1996, I was a young jobbing actor, recently out of Drama School and snotty about musicals and ‘popular’ playwrights in a rather ignorant, uninformed way. I was taken by a friend, against my will (I was also ungrateful) to see a show called ‘Company’ at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Sam Mendes and written by some guy called Stephen Sondheim who was apparently quite well-known by people who liked showtunes (ignorant, uninformed). By the end of the evening, every presumption and prejudice that I held about what musicals were - shallow, lightweight, ‘entertaining’ (meant in a derogatory sense), dissatisfying - were turned on their heads by a man who, in my newly damascene eyes, had redefined what a musical could be. Complex characters with believable, often painful motivations and dilemmas; lyrics that buzzed and electrified with keen, sometimes scathing, often warm and always wise observations about the human condition; and music, my God the music, shifting and restless, melodic and dissonant, usually together, uniting the theatrical and the deeply, humanly personal. I’ve never understood it when some people claim that Sondheim can’t write tunes. They might just as well say that Einstein can’t write formulas.

Stephen Sondheim

Of course, it turned out that this Sondheim geezer had written

quite a few things, most of the good stuff some years before I saw ‘Company’,

and this newly-addicted devotee gradually sought out most of them. The

experience of watching ‘Sweeney Todd’ at the National Theatre, with Alun

Armstrong as a sensational Sweeney and Denis Quilley (formerly a Sweeney when

younger) now an older, more disturbing Judge Turpin, was mind-expanding. This

was a London that didn’t necessarily feel ‘real’ - but as we’ve established,

‘honest’ is a better word - but it was perfect for the musical’s real purpose,

a journey into the darkness of man via jealousy, betrayal, corruption and

revenge. Was this man who created a gothic horror set in the sewer of Victorian

London, the same one who fashioned the cool New York detachment and alienation

of ‘Company’? Yes, obviously - the same tropes exist in both. The examination

of human nature (both Bobby and Sweeny are alone by choice, although both long

for companionship, past and future), the mastery of black comedy and pathos (‘A

Little Priest’ and ‘Not Getting Married’, both hilarious and dark in equal

measure, are clearly from the same stable - Paul: Honey, I can't find my

cufflinks. Amy: They're on the dresser. Right next to my suicide note),

the same savagery lurking just beneath the civilisation. The setting is

grotesquely different, but Sondheim’s preoccupations remain the same, and they

speak to us, to me. I was lucky enough to see, and hang around backstage of,

the immaculate production of ‘A Little Night Music’ at the National, with Judi

Dench as Desiree - her rendition of ‘Send in the Clowns’ was heartbreaking in

the way it captured a character who was fully aware of the absurdity of her

romantic situation, even to the extent of finding it ruefully funny, whilst

recognising that she could do nothing to alter it. When I saw Hannah Waddingham

sing the same song 13 years later at the Menier Chocolate Factory, despite the

differences in interpretation, it had lost none of its power and capacity to

evoke the quiet pain of love, alongside the other masterpiece of that musical,

‘Every Day A Little Death’. Again, the dark swells under the perfect manners

and elevated society of a Viennese country estate, disguised by musical

confections but betrayed by reflective, bittersweet lyrics, link this Sondheim

work to his others. In the same way that I am drawn to the subtextual,

psychologically truthful works of Chekhov, Ibsen and Miller, I respond, as many

others, to the flawed beauty of what Sondheim offers in ‘Merrily We Roll Along’

and ‘Follies’ - the sell-out, the unrequited, the unfulfilled, bright dreams

and lost ambitions, growing up and growing old.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.