by Isabelle Welch

Lost in communication- a brief summary of

Wittgenstein’s early works

|

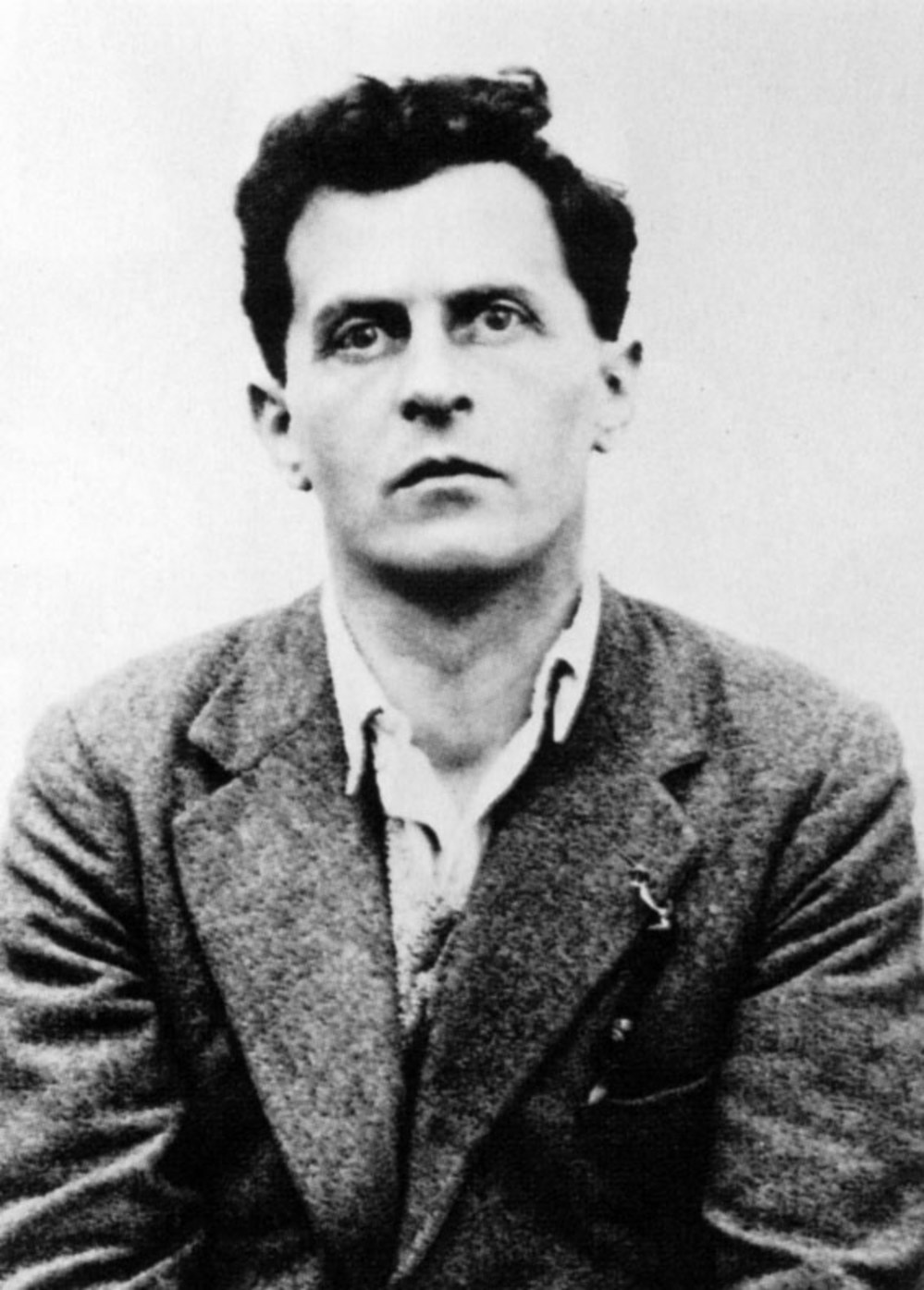

| Ludwig Wittgentein |

A lot of unhappiness in this world comes

about because we can’t let other people know what we mean clearly enough. One

of the philosophers who can help us is Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was a recluse,

he had a stutter, he would pause in the middle of sentences, and had a habit of

storming out if someone disagreed with him. Oddly perhaps, this was the ideal

formula for someone intent on studying what causes communication fails.

Wittgenstein was born in Vienna in 1889,

the youngest child of a wealthy, highly cultured, domineering businessman. Three of Wittgenstein’s four brothers

committed suicide, and w himself was frequently troubled by suicidal thoughts.

When he was young his father encouraged him down a path to engineering, which

he studied at Cambridge. Whilst he was at Cambridge his father passed away, and

he inherited a large sum of money, which he lay off to other family members and

a selection of young, ‘indie’, and often alcoholic, Austrian poets, before

moving to Norway to live in a recluse mountain hut. It was here that he

‘Tractus Logico-Philosophicus.’

‘Tractus Logico-Philosophicus.’ was a

short, beautiful and baffling work. The big question that he asked in was how

humans communicate to one another. His answer, which felt revolutionary for the

time, is that language works by triggering within us pictures of how things are

in the world. He came to this conclusion through reading a newspaper clipping

about a Paris court case in which, inn order to explain in greater efficacy the

details of a road accident, the court had arranged for the accident to be

reproduced visually: using model cars and pedestrians. It was a eureka moment.

For Wittgenstein, effective language is that,

that enables us to ‘make pictures of facts.’ For example, to say ‘the bench is

by the chip shop,’ paints a rapid sketch that, like the model, lets another

person see the situation in their mind and understand. We are constantly

swapping ‘pictures’ between us in this fashion, but the Paris court needed a

physical model for a very important reason: on the whole we are poor at

conveying accurate pictures in the minds of others.

Communication typically

goes wrong because other people have, as we put it, ‘the wrong picture’ of what

we mean. It can take an age for two people to recognize divergences over the simplest

of things. Problems of communication typically start because we don’t have a

clear picture of what we mean in our own heads. We often say quite meaningless

or muddled or unelaborated things, which therefor can go nowhere, in the minds

of others: ‘I am a spiritual sort of person.’ ‘I love fairness’ ‘I can’t even.’

There is another danger, which I’m sure any teen who has sat staring at a text

can relate too, that we read more meaning into the words of others that was

ever intended or that is warranted. You may tell your boyfriend that you had a

conversation with an ‘interesting guy,’ at last nights party, the picture in

your mind is an innocent one, but he may rapidly form a very different

impression.

The tractatus is a plea made by the awkward

Austrian to speak more carefully and less impulsively.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.