Tom McCarthy marks today's 150th anniversary of the birth of poet William Butler Yeats

Who, then was Maud Gonne, “the

beautiful Irish nationalist” about whom Yeats

wrote “ some of the most original

and poignant love poems of all time”? (Robert Mighall). For our modern age, she would be regarded as

unusual; for her own time (1866-1953) she was extraordinary.

“I was twenty-three years old when the troubling of my

life began”: this is how Yeats begins

his description of Maud Gonne on first meeting her in 1889. His Autobiography continues:

“I had never thought to see

in a living woman so great beauty. It

belonged to famous

pictures,

to poetry, to some legendary past. A

complexion like the blossom of apples,

and yet face and body had the

beauty of lineaments which Blake calls the highest

beauty...she

seemed of a divine race”.

What did she see in this young Irish writer whose first

poems had been first published in 1885?

Kathleen Tynan, his friend and a poet herself, said that he was

“beautiful to look at, with his dark face, its touch of vivid colouring, the

night-black hair, the eager dark eyes”.

She became for Yeats his inspiration, the great love and yet

the troubling of all his life.

The Hill of Howth or Howth Head guards Dublin Bay from

the north. It was a place of special

importance to Maud Gonne where she lived as a child. Later in life she wrote:

“No

place has ever seemed to me quite as lovely as Howth was then. ... The heather

grew

so high and strong that we could make cubby houses and be entirely hidden and

entirely

warm and sheltered from the high wind”.

Yeats, too, loved Howth where he lived for a short time

when he was young. In 1890 he spent a

day there with Maud Gonne and remembering that day he wrote his first poem

about her. It is an early Yeats when he

was still under the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites and it has all the lazy

beauty of Pre-Raphaelite rhythms. Of this period of his life he later

wrote: “We were the last Romantics”. The

poem is called “The White Birds”:

“I

would that we were, my beloved, white birds on the foam of the sea!

We

tire of the flame of the meteor, before it can fade and flee;

And

the flame of the blue star of twilight, hung low on the rim of the sky,

Has

awaked in our hearts, my beloved, a sadness that may not die.

A

weariness comes from those dreamers, dew-dabbled, the lily and rose;

Ah

dream not of them, my beloved, the flame of the meteor that goes,

Or the

flame of the blue star that lingers hung low in the fall of the dew:

For

I would we were changed to white birds on the wandering foam: I and you!

I am

haunted by numberless islands, and many a Danaan shore,

Where

Time would surely forget us, and Sorrow comes near us no more;

Soon

far from the rose and the lily and fret of the flames would we be,

Were

we only white birds, my beloved, buoyed up on the foam of the sea!

|

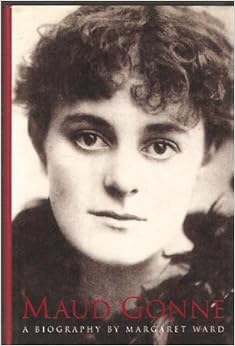

| Maud Gonne |

Maud Gonne and Ireland, hurling “the little streets

upon the great”

In her early years she moved with her family between

England, Ireland and occasionally France. At the age of 18, she was presented

at Court and was escorted onto the royal

dais by the Prince of Wales. At the age of 21, after the death of her

father, she began living an independent life in Paris where she became involved

with a right-wing group intent on destroying the Third Republic; among that

group she met Lucien Millevoye, a journalist/politician. On the group’s behalf she

travelled to Russia on a secret mission to persuade the Tsar to finance a

right-wing plot against the Third Republic;

in 1890, she returned to Ireland and met the great leader of the Irish

Republican Brotherhood, John O’Leary, who had been exiled from Ireland for

fifteen years for his part in the Fenian Rising of 1865 ( see Yeats’s “September, 1913”). O’Leary converted her to Irish nationalism,

just as earlier he had converted Yeats who remained always moderate.

Her first Irish campaign in 1890 was against the mass

eviction of tenants in the most poverty-stricken areas of Donegal; Yeats’s poem

“Her Praise”, more than twenty years later.

remembers this:

“I

will talk no more of books or the long war

But

walk by the dry thorn until I have found

Some

beggar sheltering from the wind, and there

Manage

the talk until her name comes round.

If

there be rags enough he will know her name

And

be well pleased remembering it, for in the old days,

Though

she had young men’s praise and old men’s blame,

Among

the poor both old and young gave her praise”.

In Donegal, a warrant was issued

for her arrest but later cancelled.

In Paris, she founded a newspaper called L’Irlande Libre. On a fund-raising tour of America in support

of Home Rule for Ireland, a newspaper called her “Ireland’s Joan of Arc”. She was one of the leaders of two massive

demonstrations in Dublin, first against the celebrations of Queen Victoria’s

Jubilee in 1897 and a few years later against the visit to Ireland of King

Edward VII, her former escort. On that occasion, she hung a black petticoat

outside her house in Dublin in a street festooned with Union Jacks. When a

Unionist mob invaded her house, she fought back. In “No Second Troy” Yeats

tells us:

“Why

should I blame her that she filled my days

With

misery, or that she would of late

Have

taught to ignorant men most violent ways,

Or

hurled the little streets upon the great,

During the Boer War she spoke out in Paris in favour of

the Boers against “British Imperialism”;

here she met Captain John MacBride, an Irish nationalist who fought with the

Boers in South Africa. In Dublin a pro-Boer march was banned but Gonne and a

few other Irish leaders ignored the ban. Around that time she became the first

president of Inghinidhe na hEireann, (Daughters of Ireland), a group of women

dedicated to promote Irish culture and Home Rule for Ireland. She was one of the leaders in a campaign to

extend free school meals for Irish schoolchildren, a campaign that succeeded in

1912.

In late 1914, Maud Gonne began working as a Red Cross

nurse in a French military hospital where she became aware for the first time

of the reality of war:

“...in my heart is growing up a wild hatred

of the war machine”.

The Easter Rising

in Dublin in 1916 began and failed with the executions of all but two of its

leaders (see “Sixteen Dead Men”). Stranded in France, she was desperate to go

to Ireland, but as soon as she arrived in London she was served with a notice

under the Defence of the Realm Act, exiling her from Ireland. Nevertheless, eventually she travelled to Dublin in disguise; she was

arrested in 1918 and sent to Holloway

Prison where her companions included Constance Markiewicz, (nee Gore-Booth),

one of the two reprieved leaders of the Easter Rising, and Kathleen Clarke, the

widow of one of the executed men, Tom Clarke. This is how Yeats remembers

Constance in his “In Memory of Eva

Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz”:

“The

light of evening, Lissadell,

Great

windows open to the south,

Two

girls in silk kimonos, both

Beautiful,

one a gazelle

A later poem “On a Political Prisoner” is more sombre.

In 1921, the

Anglo-Irish Treaty divided Ireland into North and South. A government which accepted the Treaty’s

division of Ireland was formed; tragically a bitter and shameful civil war

began between former nationalist fighters, between those in favour of the

Treaty and those against ( see “Meditations in Time of Civil War”). A group of

women in Dublin, including Maud Gonne, set up a Peace Committee to reconcile

the two sides, but the Government was pitiless in its violence against former

comrades. With her Peace Committee she

led huge and noisy demonstrations against the Irish Government that was

imprisoning and executing anti-Treaty campaigners. She wrote in her Memoirs:

“We

claimed, as women, on whom the misery of civil war would fall, that we had a

right to

Be

heard”.

Her home was ransacked by a pro-Treaty crowd...as it had

been under British rule years earlier. She was arrested twice by the new Irish

Government and on the second occasion she was released after going on hunger

strike. She went to Northern Ireland to

see for herself the distressed conditions of Catholics driven from their

homes: she was arrested and deported

back to Dublin. With her Peace Committee

a Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League was set up to support the families’ of

imprisoned anti-Treaty men and women. It was eventually banned by the Irish

Government but continued to meet and campaign under a different name. She spent the rest of her life as a fervent

campaigner for refugees and for prisoners’ rights.

Maud Gonne; Millevoye; MacBride; Yeats: “Love fled...and his his head among a

crowd of stars”

The most astonishing fact about this “beautiful Irish

nationalist” was that she was English, born in Tongham in Surrey in 1866. Her father, Tommy, was an English army

captain and later colonel, sent to Ireland with his wife and two daughters when

she was two years old. Yet she was a very

private person and her own private life had its deal of troubles and its secrets.

After the death of her father, it was John O’Leary,

almost a father-figure, who converted her to Home Rule for Ireland. She moved

equally between Dublin and Paris, having ample means to lead an independent

life. In Paris in 1887, she began a ten-year relationship with a married

right-wing French politician, Lucien Millevoye; it was on his behalf that she

went on that secret mission to Russia.

By the time she met Yeats in 1889, she already had a son named George

who had died when he was one. By the

time Yeats had proposed to her twice, she had a daughter named Iseult whom she

passed off as her niece. No one, least of all Yeats, in Ireland knew any of

this.

Yeats and Gonne were opposites in many ways. A contemporary wrote of Yeats that “He

wanders in the realms of the mind”; Gonne says of her life at the time she met

Yeats: “...it was one of ceaseless activity and travelling. I rarely spent a month in one place”. Over a

period of twelve years he proposed to her on five different occasions. In her Memoirs

she recalls that on one occasion she told him:

“You make beautiful poetry out of what you

call your unhappiness and you are happy

in that...Poets should never marry. The world should thank me for not marrying

you”.

Yeats’s poem “Words” recalls this unwelcome advice:

“That

had she done so, who can say

What

would have been shaken from the sieve?

I

might have thrown poor words away

And

been content to live”.

In November 1898 in Dublin she finally confessed to Yeats

the details of her relationship with Millevoye; he wrote no poems for a year.

In Paris Maud Gonne was active in pro-Boer propaganda.

There she had met and admired John MacBride in 1900, an Irish hero to Irish

nationalists because he fought against the British forces in the Boer War. In

1903, she converted to Catholicism and suddenly and unexpectedly married

MacBride in Paris in February, she so unconventional, he as an Irish man of his

time, so full of conventions about a woman’s place, always second. It was she,

not the best man, who gave the final toast at their wedding reception; she insisted on keeping her own name, too.

A few days later in Dublin, as he was about to give an

evening lecture on the future of Irish drama, Yeats received a telegram,

informing him of her marriage. Afterwards he remembered nothing of the lecture

as he walked alone the streets of Dublin, devastated by what he saw as

betrayal. “Reconciliation”, written in

1908, recalls that night:

“Some

may have blamed you that you took away

The

verses that could move them on the day

When,

the ears being deafened, the sight of the eyes blind

With

lightning, you went from me, and I could find

Nothing

to make a song about but kings,

Helmets,

and swords, and half-forgotten things

That

were like memories of you – but now

We’ll

out, for the world lives as long ago;

And

while we’re in our laughing, weeping fit,

Hurl

helmets, crowns, and swords into the pit.

But,

dear, cling close to me; since you were gone,

My

barren thoughts have chilled me to the bone

Her sudden decision to marry MacBride was followed a year

later after the birth of their son, Sean, by a decision to divorce him, citing

drunkenness and cruelty. For Catholics

divorce was not possible, so in the end there was a judicial separation in

1906. The Irish nationalists now turned

against her, blaming her. O’Leary, her mentor and the godfather of her son,

took MacBride’s part. Lady Gregory, Yeats’s partner in setting up the Abbey

Theatre, wrote that “I think that her work in Ireland is over for her”.

Yeats was the only person who stood by her. He wrote to Lady Gregory that “The trouble

with these men (Irish nationalists) is that in their eyes a woman has no

rights”. On her return to Dublin after

the separation, she went to the Abbey Theatre, escorted by Yeats for a

performance of Lady Gregory’s “The Gaol

Gate”. This great campaigner for Irish independence was hissed at by this

Irish audience. She turned, smiling, to face her attackers; Yeats was enraged,

(see the words of “my phoenix” in his poem “The People”:

“The

drunkards, pilferers of public funds,

All

the dishonest crowd I had driven away,

When

my luck changed and they dared meet my face,

Crawled

from obscurity, and set upon me

Those

I had served and some that I had fed;

Yet

never have I, now nor any time,

Complained

of the people.”

For ten years Maud Gonne was cold-shouldered by the

nationalists, yet she continued working on Irish causes.

Yeats proposed again for the sixth time; she offered him

a “spiritual marriage” which he accepted but privately was utterly frustrated,

(see his bitter poem “Presences”). The

final stanza of “Adam’s Curse”, which he had written much earlier, now seemed

prescient:

“I

had a thought for no one’s but your ears:

That

you were beautiful, and that I strove

To

love you in the old high ways of love;

That

it had all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown

As

weary-hearted as that hollow moon”.

The culmination of centuries of struggle for Irish

independence took place in the Easter Rising of 1916. Within a week the

rebellion was crushed and its leaders executed, John MacBride among them. “Easter 1916” is Yeats’s response. Maud Gonne returned to Ireland as soon as she

could as Maud Gonne MacBride, thus joining that highly respected group, that of

the nationalist widows of that 1916 and she was accepted once again.

In 1917 Yeats at the age of 51 married Georgie Hyde-Lees

in London. Gonne MacBride was quite happy at this. Indeed while she was in prison in Holloway

she offered her Dublin home to the married couple. They had two children, a

daughter, Anne, and a son, Michael.

Last Years:

“There is grey in your hair”

Once Ireland won its independence in 1921, her friendship

with Yeats cooled over political differences. She was opposed to the pro-Treaty

Irish Government and he served as a Senator from 1922-1928. He himself, as a Protestant, had always been

opposed to her Catholicism. When he

resigned from the Senate, they resumed their friendship, though never as

ardently as before.

She is never named in all the poems about her, however in

“Beautiful Lofty Things”, written in 1937, two years before he died – not

a love poem – Yeats names her among all

the people and experiences that made life meaningful for him and that made him:

“Beautiful

lofty things, O’Leary’s noble head,

My

father upon the Abbey stage, before him a raging crowd:

‘The

land of Saints’, and then as the applause died out,

‘Of

plaster Saints’; his beautiful, mischievous head thrown back.

Standish

O’Grady supporting himself between the tables

Speaking

to a drunken audience high nonsensical words;

Augusta

Gregory seated at her great ormolu table,

Her

eightieth winter approaching: ‘Yesterday he threatened my life.

I

told him that nightly from six to seven I sat at this table,

The

blinds drawn up’; Maud Gonne at Howth

station waiting a train,

Pallas

Athene in that straight back and arrogant head:

All

the Olympians; a thing never known again”.

So there she is, at the end of his life, as she was at

the beginning. In pride of place at the

end of his own Panathenaea, Maud Gonne, “of divine race”, Pallas Athena

herself, the last of the Olympians.

Bibliography:

YEATS by Richard Ellmann; W.B. YEATS by Alasdair Macrae; A PREFACE TO YEATS by Edward Malins and John

Purkiss; COLLECTED POEMS OF W.B. YEATS

by Robert Mighall; MAUD GONNE by

Margaret Ward.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.