by Liliana Nogueira-Pache

|

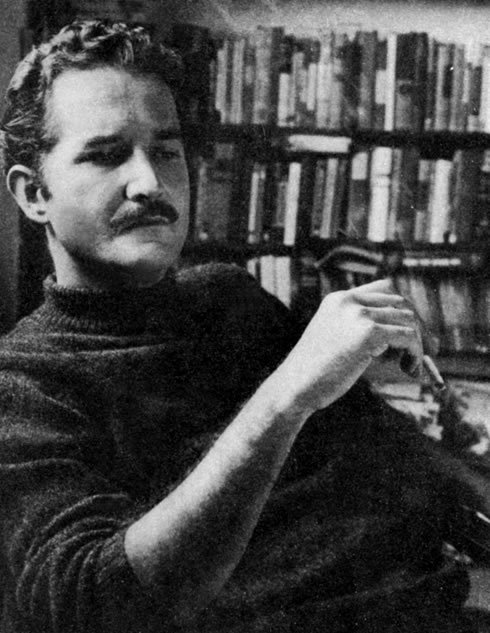

| Carlos Fuentes (right) and Gabriel Garcia Marquez |

Bilingual from a young age, Fuentes had written essays and short stories by the age of 11; he was 18 when he won the first, second and third prize in a literary competition at his school in Mexico

His first novel, La Region Más Transparente (1958) was extraordinarily well received, a success that has not diminished in nearly fifty years. It is an urban novel, an analysis of a reality that is no longer transparent --- exploring a capital consisting not just of a ferocious reality but also memory. But Fuentes does not only regret. The dust of his beloved city doesn’t blind him or choke him, and, although it is no longer transparent, his words will find a way to fight against injustice and corruption, just as his Gringo Viejo (1985) did. His language, passionate and beautiful, would be his weapon.

Always the past. Spain in Mexico

“Spain for the Spanish is like Mexico for the Mexicans, a painful obsession. Not a hymn to optimism as their country is to North Americans, nor a phlegmatic joke as it is for the English, nor a sentimental madness – the Russians – nor a reasonable irony – the French – nor an aggressive mandate as it is for the Germans, but a conflict of halves, of opposites, a tugging of souls, Spain and Mexico, countries of sunshine and shadow.”

His posthumous novel Federico en su Balcón (to be published at the end of this year) is the end of a voyage that starts with questions to try and find out who he is. In La Muerte de Artemio Cruz (1962) Fuentes gives three voices to Artemio, who is about to die, and it becomes a pilgrimage between the present, the past and the future. There is the conscious self, narrated in the first person, his conscience narrated in the second person and the life of Artemio in the third person, which culminates in his “We shall die…You…are dying, you have died … I shall die” with which the novel ends. Perhaps Dante Loredano, the mirror of the author in this last novel, who debates with his neighbour Federico (Friedrich Nietzsche), is but a reflection of Artemio in the other. But although the man died on 15th May, his essence will never leave us. It teaches us that we, too, should never stop asking questions.

Carlos Fuentes Macías (Panama 11 November 1928 – Mexico 15 May 2012)

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments with names are more likely to be published.